Let’s segue a bit from the main focus of the blog (which if you don’t know is data science applied to entertainment) to focus on something closer to home — data science on the Philippine government.

Don’t get me wrong. I have no intention of turning my blog into a political platform. In fact, I hate talking about politics.

There are two reasons why this post exists. One, I found a fabulous dataset, which is rare in the Philippines as my last intern can attest. Two, I have a newfound interest in quantitative social science, particularly of the applied NLP flavor.

In this post, I zoom in on Senate bills over the 13th Congress (2004) to the 17th Congress (2016). The nature of Philippine elections dictates that Congress constituency changes three years at a time. Senators serve six-year terms, with half elected every three years.

I focus on two questions:

- What general topics do Philippine senators write bills on?

- How do these topics change from Congress to Congress?

By topic in the first item, I mean the general gist of the bill. Is the bill about education? About prohibition?

And by the second bullet, what I mean is whether the number of bills about health, for example, change as Congress constituency change. Does it increase from 2004 to 2016?

Answers to these two questions give us some clues on the issues that the Philippine Senate is focusing on. Does the Senate prioritize new taxes over healthcare? New holidays over new public projects? These are some sample questions that I aim to answer in this post.

Web Scraping and Text Preprocessing

Conveniently, the Philippine government maintains a database of proposed Senate and House bills from the 13th to 17th Congress. With some delicious BeautifulSoup, I was able to extract the pertinent information from the website: the title of the bill, the description of the bill, the year it was filed, and the authors of the bill. In total, I recovered 14,741 Senate bills proposed from June 30, 2004 to May 23, 2018.

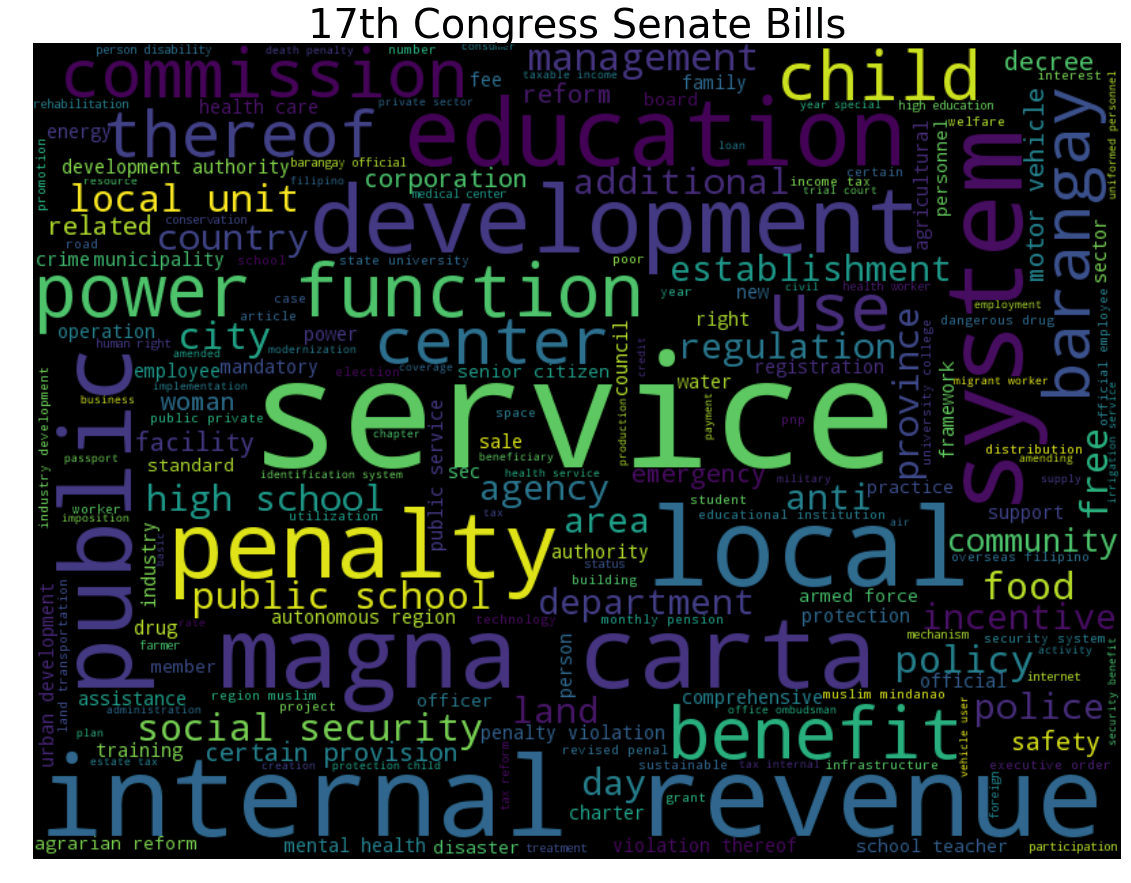

Word Clouds

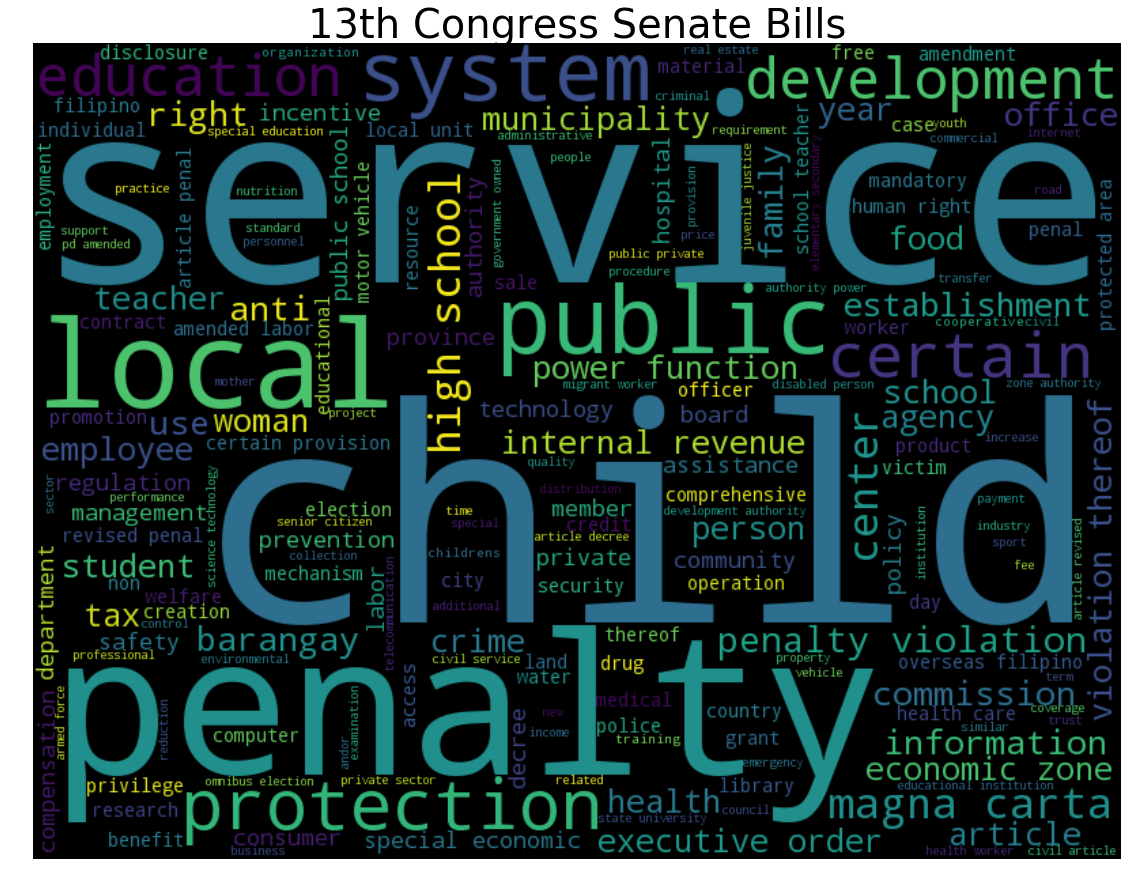

Let’s start with something basic to understand the data: visualization. Let us look at the word clouds for each Congress.

For this part my focus is on the textual content of the bill, and so I concatenated the title and description of each bill and used that to characterize the bill. There is rich information contained in the author data, and we will look into that in the next section. For now I focus on the title and description.

The canonical package for Natural Language Processing in Python is NLTK.

Standard preprocessing steps I applied are as follows:

- removal of punctuation

- word tokenization

- p(art) o(f) s(peech) tagging (retaining only nouns and adjectives)

- lemmatization with Wordnet

After getting the data in clean and pristine form, I removed some words that appeared a lot of times in the corpus. For example, I removed the word ‘act’ since it appeared in almost all Senate bills. These are called domain-specific stop words, and it’s important to remove these since these tend to dominate less frequent but more informative words.

After preprocessing, I converted the text into their Bag-of-Words representation for further processing.

Keywords for the 13th Congress are service, child and penalty. Some bills filed by this Congress are

- Vision Care for Kids Act by Miriam Defensor-Santiago : “… establish a grant program to provide vision care to children …”

- Anti-Neglected Children’s Act of 2007 by Miriam Defensor-Santiago : “… penalize the neglect of a child by parents …”

- Service of Warrants of Arrests in Certain Cases Prohibition by Juan Flavier: “… prohibiting the service of warrants of arrests in certain cases and providing penalties for violations …”

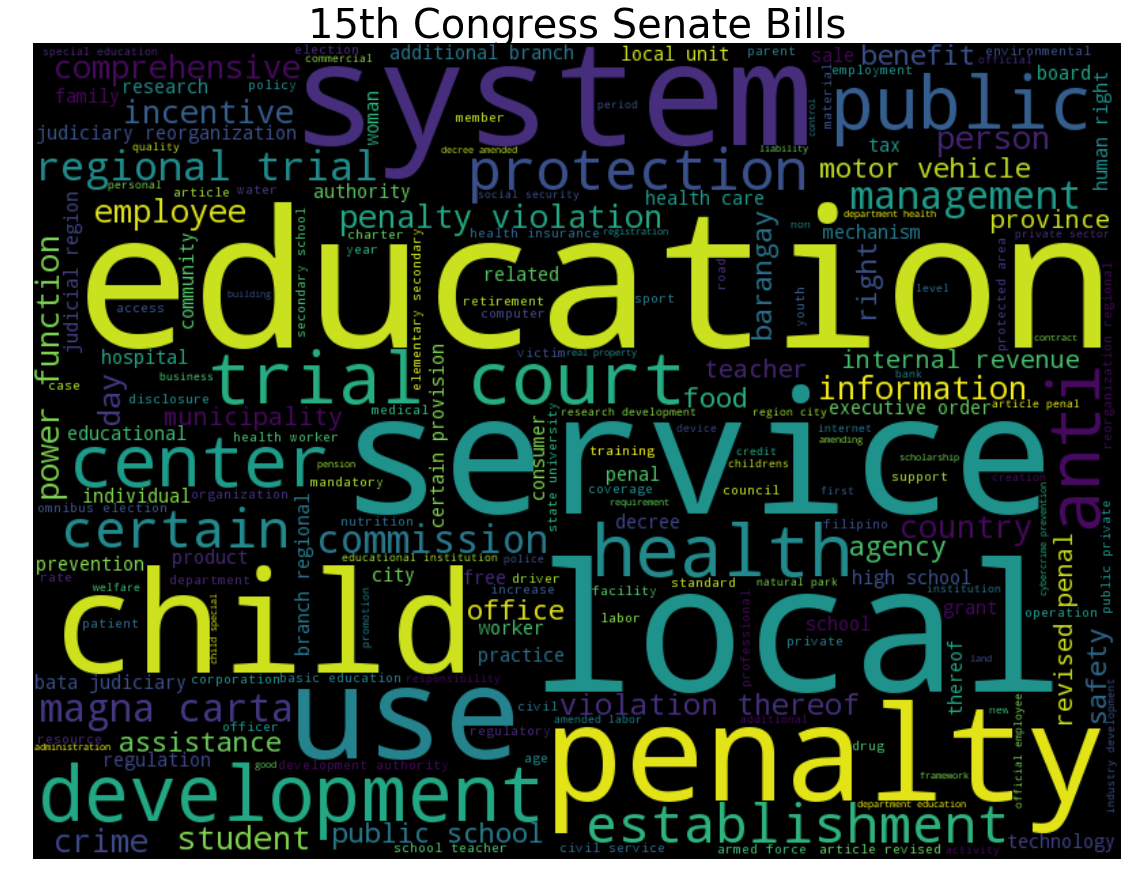

Here, apparent keywords are education, service, local. Some example bills passed during this time are:

- Scholarship Grants to PNP, AFP, Bfp, Bjmp Family Members by Ramon Revilla Jr.

- Universally Accessible Cheaper and Quality Medicines Act by Loren Legarda

- Silent Mode Act by Miriam Defensor-Santiago

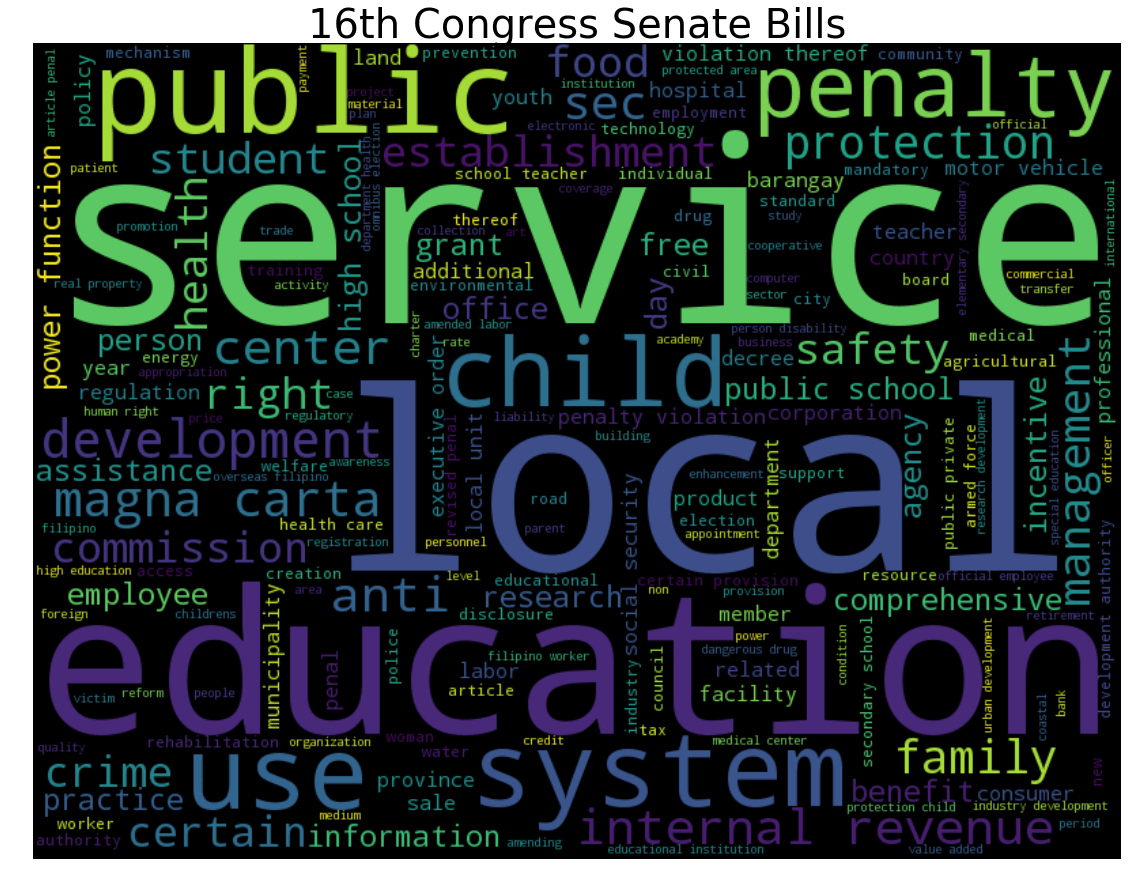

Again, service, local and education are apparent keywords during the 16th Congress. Some sample bills filed during the Congress are:

- Consumer Protection Act by MDS

- Anti-Distracted Driving Act by Ejercito-Estrada

- Sustainable Transportation Act by Pia Cayetano, etal.

No keyword pops out. Well, except for service. This is the current ruling Congress, and here are some representative bills:

- Anti-Hazing Act by Honasan

- Public Safety Act by Sotto

- Transportation Crisis Act of 2016 by Drilon

The word clouds in the last section are pretty… but not really very informative. At this point, we’re at the visualization phase of our data science pipeline.

Topic Modeling of Senate Bills

In the last section, we saw which words appeared frequently in the bills filed per Congress, but we also noted that word clouds don’t really allow us to identify the topics and quantify the topic proportions each Congress focused on. Since word clouds are mainly for visualization and not for actual modeling, we have to resort to a different method.

Enter topic modeling.

Topic Modeling Fundamentals

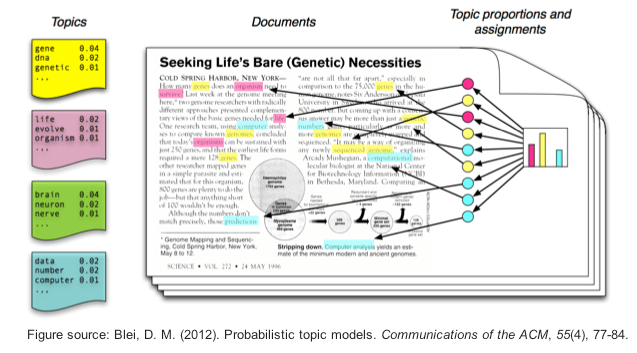

Topic modeling is an unsupervised learning technique to discover hidden topics in a set of text documents. The math behind topic models is quite involved, so we’re not going to focus on that here. As we’re mostly focused on the end result, it’s more important right now to use the model and understand what the results mean.

To make it easier for everyone, let me give an concrete example of a topic model in action. Suppose you have a digitized set of Philippine news articles from Manila Bulletin. Feed it into a topic model, and it will discover clusters of words that constitute ‘topics’. For example, one cluster could contain words like ‘GDP’, ‘stocks’, ‘PSEI’ — these words signify the topic ‘economy’. Another cluster could contain words like ‘celebrity’, ‘Kris Aquino’, ‘KathNiel,” which are all about entertainment.

*A technical note: a topic model doesn’t actually cluster words together. For each topic, the model defines a probability distribution over all words and assign high probability to words that are relevant to the topic.

For an example study on a topic model applied to Hackernews, check out Diving into Data.

So what can you do with this set of discovered topics? For one, you can decompose an article into its constituent topics. An article talking about Kris Aquino entering Philippine politics might be labeled by a topic model to be 60% entertainment and 40% politics. This is somewhat quite remarkable since you didn’t give the topic model any context on entertainment and politics — you just fed it a set of unstructured and unlabeled text. The combination of probability theory and a ton of text data allow us to discover meaning behind text.

When someone talks about topic model, most of the time what he’s refering to is the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model, a specific type of topic model that works quite well with minimal training effort. For a very intuitive explanation of how LDA works, check out Edwin Chen’s article. Python has a very nice library called Gensim, dubbed Topic Modeling for Humans, that makes it 100x easier to build topic models out of raw text data.

Implementation and Technical Notes

To use a topic model, you need to specify the number of topics K to discover. Here I arbitrarily set K = 15. Not all topics discovered will be interpretable, and I will only retain those that appear to be coherent.

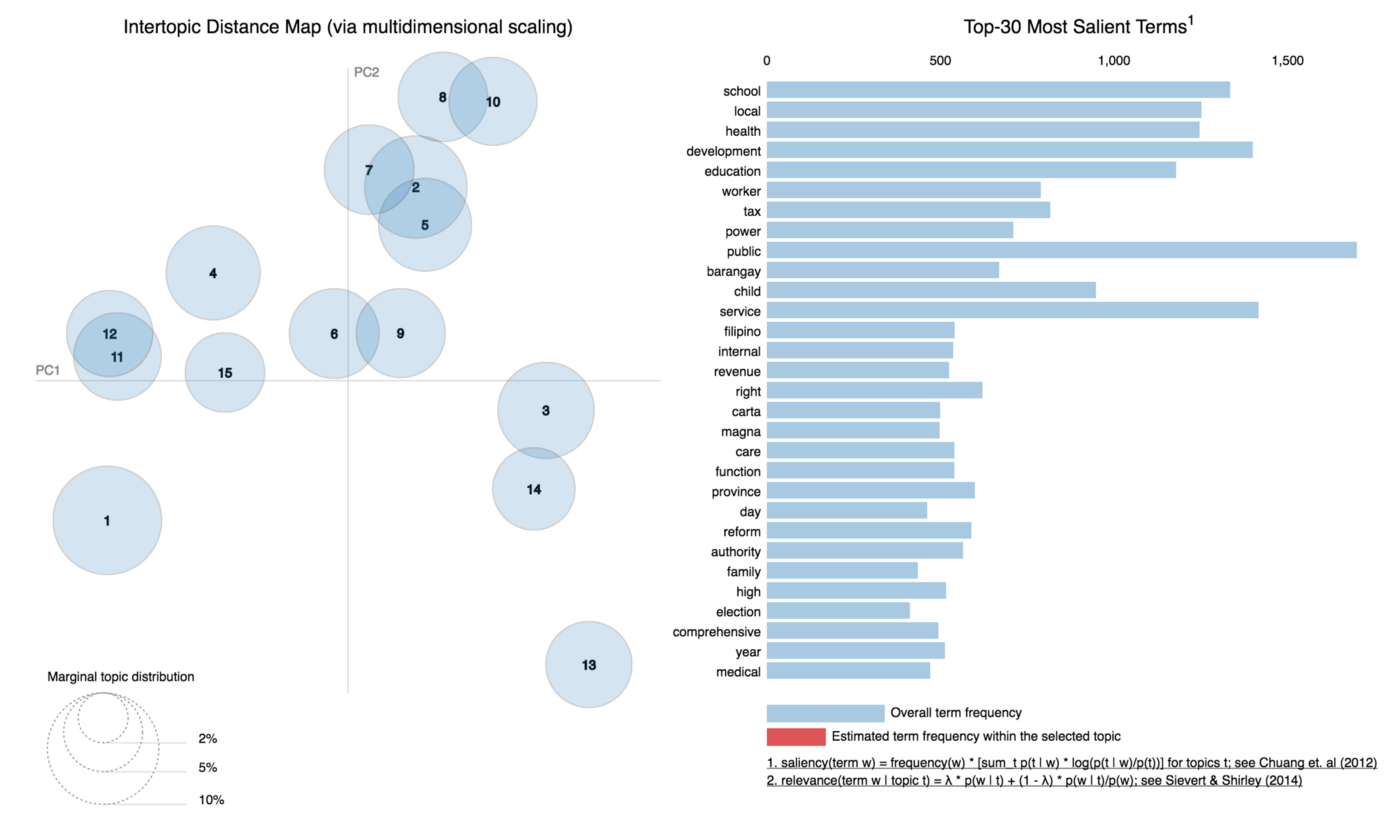

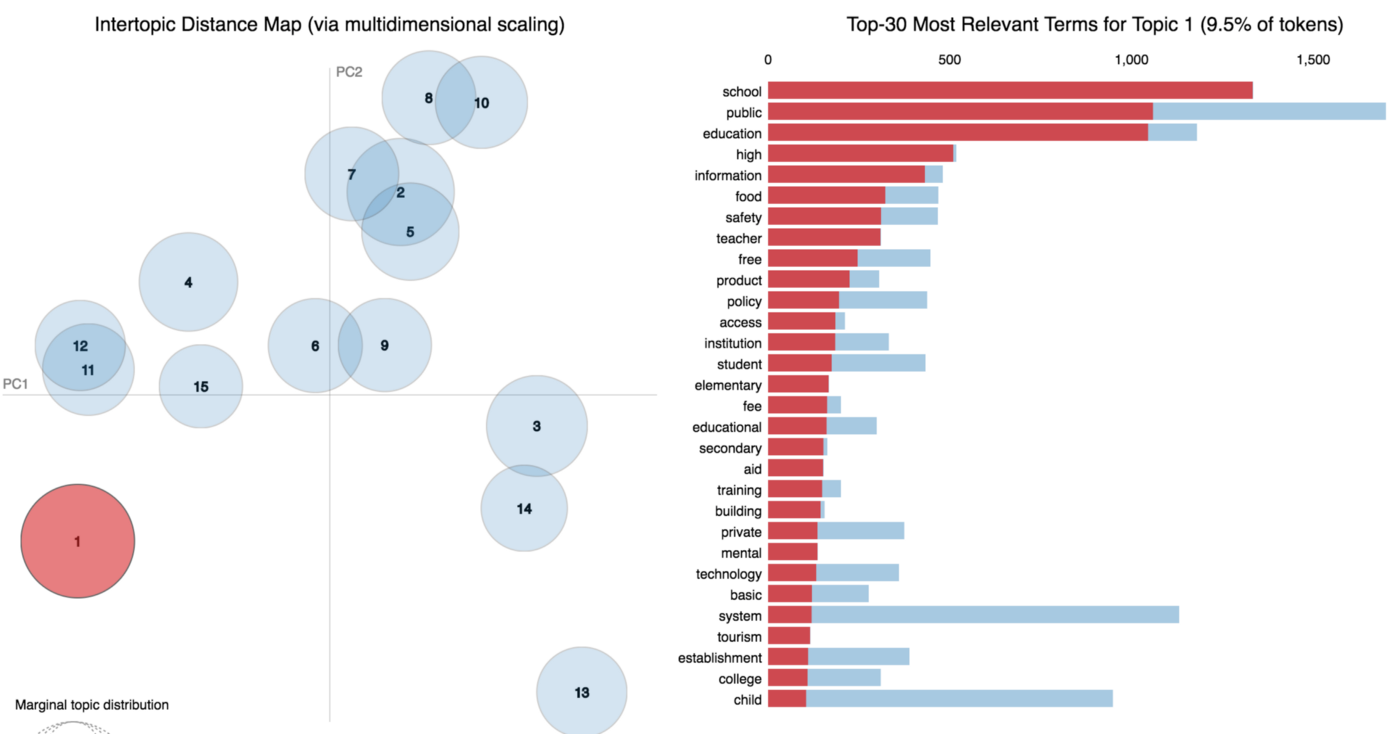

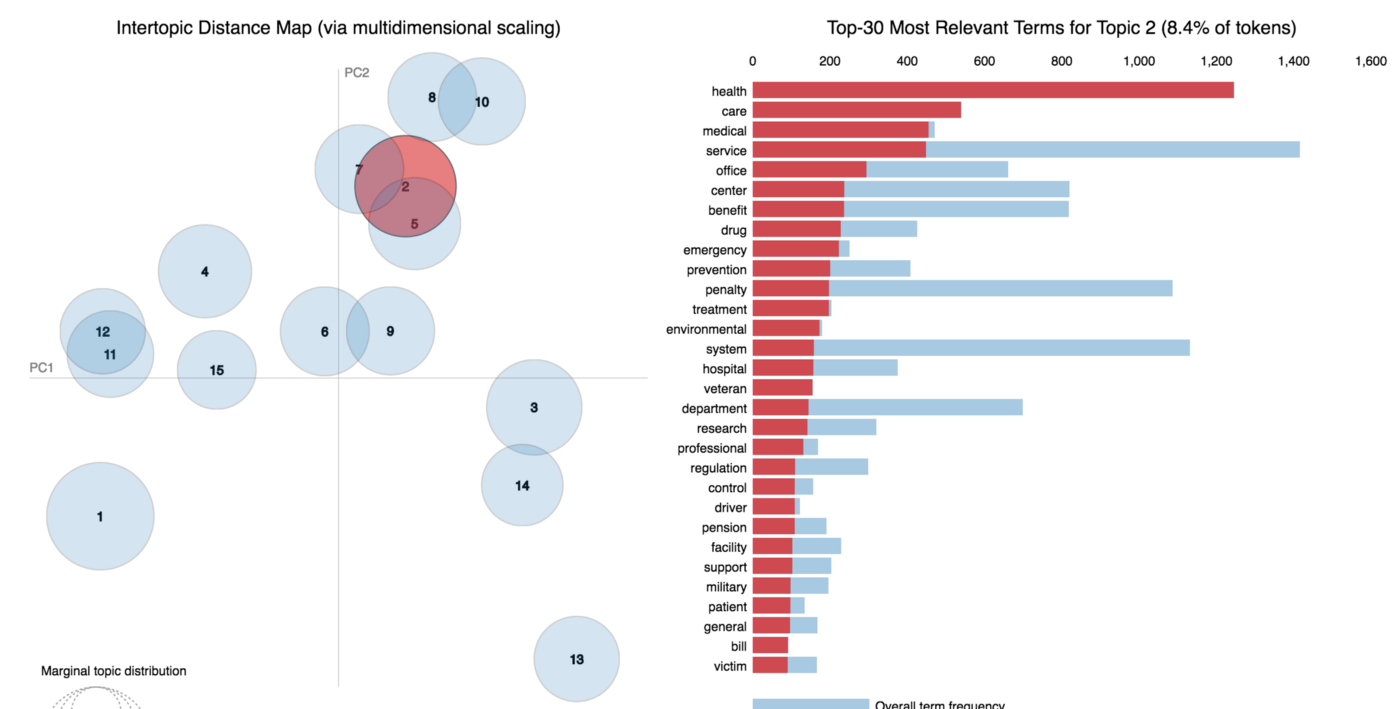

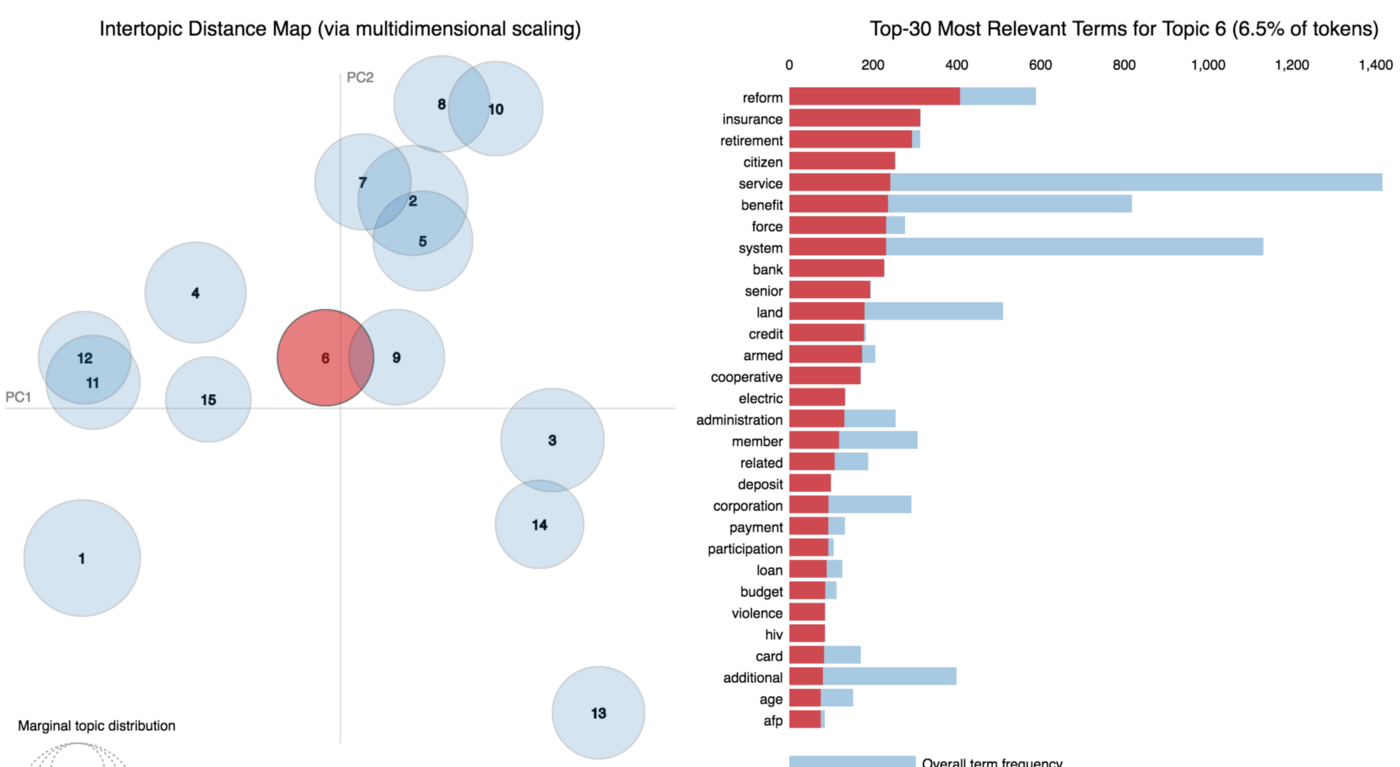

I’m using a cool tool called pyLDAvis to visualize the discovered topics in a two-dimensional bubble map. pyLDAvis also helps in the interpretation of the discovered topics.

I didn’t really focus that much on tuning in this post. But assuming I had unlimited computing power, I would probably try out different random seeds and pick the model that has the most interpretable topics. Some would advocate using the coherence model to arrive at the optimal model, but that didn’t really work that well by experience.

The focus of this post is to demonstrate how advanced NLP techniques can be used in quantitative social science, as applied in the Philippine setting. As such, we can make do with a less-than-perfect model.

Results

My Jupyter notebook contains code detailing how to construct the pyLDAvis bubble plot of the discovered topics. Let’s look at some sample topics.

Based on the top-ranking words, it’s not difficult to see that the first topic is on education.

Topic two looks like it focuses on health.

We can go through each bubble and interpret what the discovered topics mean. Not all topics are coherent. For example, topic six seems to be confused.

From the 15 topics discovered, I was able to interpret 12.

Temporal Dynamics of Senate Bill Topics

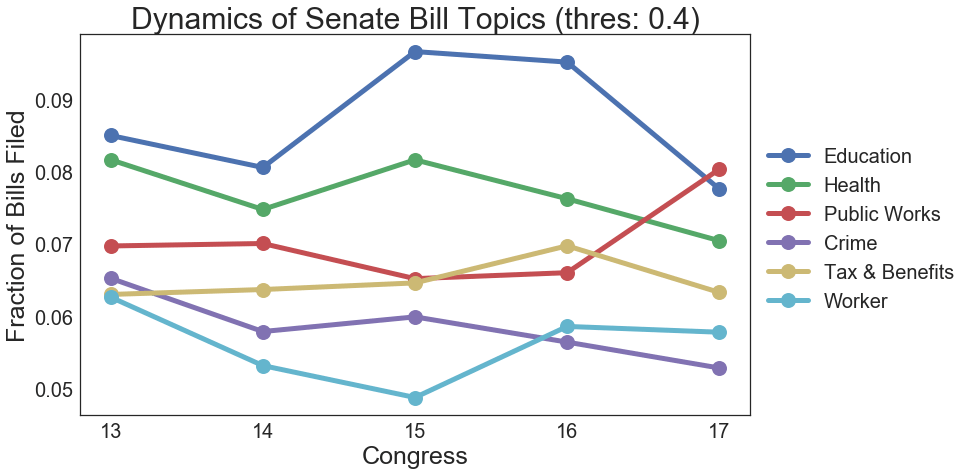

Given the discovered topics in the last section, we can plot how bill topics change from Congress to Congress.

Remember how the topic model is able to split a text into its constituent topics? In our analysis, a bill is considered to be of topic X if it is at least 40% topic X. By counting up all the bills belonging to topic X for each Congress, we are able to see to what extent Senate focuses on topic X. Note that the number of bills filed by each Congress differs (due to a number of reasons). In order to put everything in same terms, I normalized counts by total bills filed.

Here are the top six bill topics. I didn’t plot everything because a lot of the lines overlapped and I didn’t want to confuse people.

In terms of magnitude, education bills dominate the Senate, followed by health. We can see here that focus on education picked up during the 15th and 16th Congress, whereas health and crime dwindled over the years. There seems to be a resurgence in public works and worker bills based on the analysis. Lastly, tax and benefits seem to be quite stagnant.

What’s the Point?

Why not just label each bill’s topics manually? Why go through the hassle of learning Gensim and topic models to discover and label topics?

Obviously it just takes too long. Why not just let a machine do it for us?

Although the topic model cannot guarantee 100% performance in accurate labeling, it is unsupervised afterall, the knowledge discovered and the speed associated with automatic labeling make it worth the effort.

This type of study generates discussion points. Is the focus of the Congress right for the nation, or is there something else that needs to be given more attention?

Way Forward

Here are some other things that can be done to extend the results.

- Take into account the temporal differences of the Senate bills. In other words, we can integrate the information on which Congress filed which bill into the model. This will allow us to see how topics change over the years. For this case, we can use dynamic topic models or DTMs.

- Use author (senator) information in some way. It would also be interesting to see author information used in the model. This could be something basic like a comparison of the number of bills proposed by each senator, to something advanced like an application of the author-topic model, which discovers a distribution of topics filed by each author similar to how a vanilla topic model assigns a distribution of words to each topic.