The proliferation of e-commerce websites such as Amazon and content-based subscription services like Netflix and Spotify has made it essential that the right product or item is delivered to the right customer. This is one area where data-driven approaches shine. In a nutshell, we want to answer the following question:

What product should we recommend to the customer?

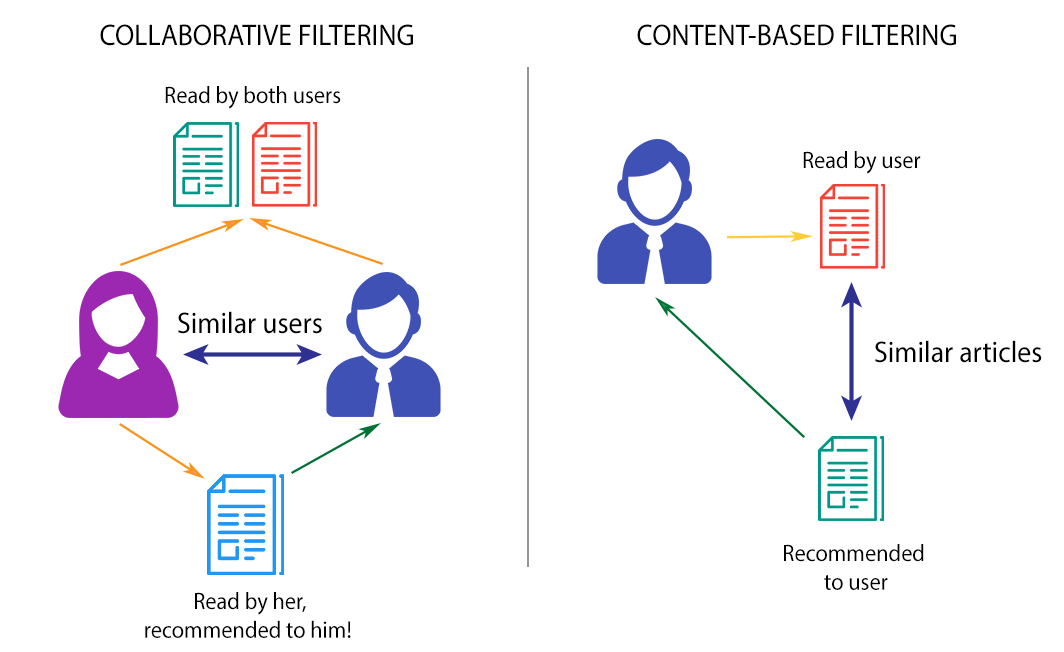

In general, there are two approaches:

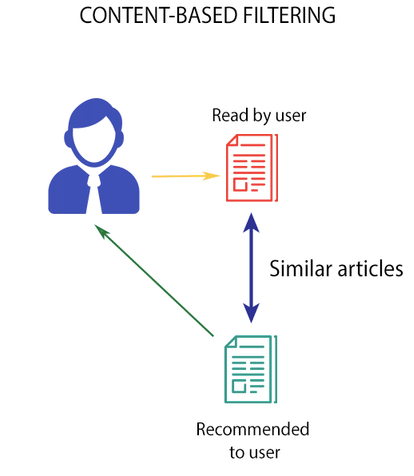

- Look at the set of products and use product information to find similar products. When a user opens a link to a specific product, recommend the top 5 products most similar to the viewed product. This approach is called content-based since we are looking at the product, not at the customer.

- Look at the transaction history of your customers. For a specific customer, find customers with similar transaction history and recommend the top 5 products that similar customers bought. This approach is called collaborative filtering since we’re taking into account user-product interactions and collaboration among customers.

Content-Based Recommendation Systems

Content-based systems leverage product information or metadata for its recommendations.

If a person looks at the book Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom on an online bookstore, a content-based system would probably recommend The Five People You Meet in Heaven or For One More Day because it would look at the author field.

There are many ways we can build a content-based system. The limit is usually set by the amount of data we have on our products.

For a given product, we build a vector composed of features derived from the available metadata. Features could be the category it belongs to (Appliance vs Fashion), the year it was published (if you are selling books), or the actors involved (if we’re recommending movies). Once feature vectors are defined for all products, we can get the (cosine) similarity among all products in the database. Given a specific product, we can find the top 5 most similar items and recommend these items once a customer looks at the product in question.

Usually, the tools of Natural Language Processing are very useful for content-based systems since products are usually accompanied by text descriptions. What we need to do is transform the text into features. There are two approaches: bag-of-words (BOW) models and embedding models.

Bag-of-word models do not take into account the context of the word, so good man and man good are the same from the BOW point of view. On the other hand, embedding models like Word2Vec and Doc2Vec transform words an documents into dense vectors which encode context and meaning. Word2vec discovers relations like king + woman — man = queen.

More sophisticated models also take into account the image of the item. For this, tools in Computer Vision such as convolutional neural networks can be used. The upside to content-based methods is that we don’t really need a lot of transactions to build the models — we just need information on the products. The downside is that the model doesn’t learn from transactions, so the performance of traditional content-based systems don’t improve over time.

Collaborative Filtering

Collaborative filtering leverages product transactions to give recommendations. For a specific customer, we find similar customers based on transaction history and recommend items which similar customers seemed to like.

One usual approach to carry out collaborative filtering is non-negative matrix factorization (NMF). We first construct the sparse interaction matrix I which has customers in its rows and products in its columns. We decompose I to a product of two matrices C and P^T. Here, C is the customer matrix, wherein each row is a customer and each column is the affinity of the customer to the latent feature discovered by the NMF. Similarly, P is the product matrix, wherein each row is a product and each column is the extent the product embodies the latent feature. These latent features are discovered by the NMF procedure.

It is up to us to decide how many latent features we want for the factorization. For example, suppose that we want 2 latent features in our movie recommendation engine. Latent feature discovered by NMF could be if whether the movie is a horror movie (that’s latent feature one) or whether the movie is a romance movie (latent feature two). A row of C then represents the customer’s affinity to horror and romance, while a row of P represents the extent the movie belongs to horror and romance. Similar to content-based systems, we can measure the similarity of these two vectors with cosine similarity to infer how much each customer likes each movie. Using that information, we can recommend movies to users.

When people mention recommendation systems, what they usually is collaborative filtering. This type of model leverages transaction data, so its performance improves over time as more and more transactions are made. This is its advantage over content-based systems. The downside is that this method is very transaction-dependent. If our online store is new, we cannot expect to give good recommendations since we don’t have anything to base them on yet. This is called the cold start problem.

Hybrid Systems

Hybrid systems leverage both item metadata and transaction data to give recommendations. There are many ways we can mix and match collaborative filtering models and content-based models. One such model is called Light FM, made by Lyst.

Light FM Explained

What I particularly liked about Light FM is that it makes use of all available information from customers, from products, and from transactions to come up with a recommendation. Since the Lyst paper is a bit esoteric on the math, I think there’s some value in explaining the model in a simpler manner.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume that we want to build a recommendation system for movies, similar to Netflix. Light FM asks three things from us:

- information on our movies. For example, year released, lead actor or actress, genre

- information on our customers. For example, age, sex, civil status

- information on movies the customers watched. Did Sally watch mother!?

Given these info, Light FM is able to give a recommendation. The content-based part here is due to the first two bullets. We represent the movies and customers with a set of distinct features. We use these features to describe the items, similar to a content-based system. The third bullet is the collaborative-filtering (CF) component. CF models tend to work well even if we don’t have information on our products or customers, granted we have tons of transaction data. But in the case of a new website, there are only a few transactions, and CF models tend to do bad (i.e. the cold start problem).

So how does the Light FM model integrate these three pieces of information?

In a usual CF model, we “discover” latent features which characterize each movie based on the customer-movie interactions (which we collect into a vector called m), and we “discover” the affinity of each customer to each latent feature discovered (which we collect into a vector called c). This is done through a process called nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF). The pairing score given to a pair of customer and movie is measured as simply the cosine similarity (basically the overlap) between vectors m and c.

The NMF procedure is an example of an embedding procedure. An embedding finds hidden (or latent) structure from the data. So NMF might discover that Deadpool is 30% action, 30% superhero and 40% comedy, and that Sally likes 10% action, 20% superhero and 70% comedy. Then the Sally-Deadpool score is the overlap between the two vectors. Movie recommendations for Sally can be made by computing the similarity of Sally’s latent features to all movies and then picking the five movies with the highest similarity.

In the case of Light FM, instead of finding latent representations of movies and customers directly, we instead get the latent representation of each feature for every movie and customer. Following this idea, the latent representation of a movie is just the sum of the latent representations of the movie’s features. Similarly for customers, we just add the latent representations of the customer’s features to get the latent representation for a customer. The score for a movie-customer pair is, again, the cosine similarity of the latent representations of the movie and the customer.

For example, if we only define three features for our movie set, say scariness, funniness, and “drama”ness (which are measured from -1 to 1), the Light FM model might discover the latent features that (1) relate to the color profile of the movie (say -1 is monochrome and 1 is super colorful) and (2) relate to the number of deaths in the movie (again, -1 for no deaths and 1 for many deaths).

Suppose that we feed the model the data that we have and wait for it to finish running. The model is then able to infer that the latent representation for scariness is (-0.8, 0.9) since scary movies tend to have very muted colors and many deaths, for funniness (0.9, -0.7), and for dramaness (0.6, 0.9).

So for example, Before Sunrise in terms of its features could be given a representation (0, 0.5, 0.8). And so, its latent representation in terms of Light FM is the weighted sum of the latent vectors of its features. That is, 0*(-0.8, 0.9) + 0.5*(0.9, -0.7) + 0.8*(0.6, 0.9) = (0.93, 0.37). Based on our representation, Before Sunrise is quite colorful and doesn’t involve a lot of death.

We can do the same for the users. The features of each user are represented in terms of a latent vector that contains the affinity of the user to color and deaths. The user is then represented as the sum of the latent vectors of each of its features.

Finally, we can measure the affinity of the user to a specific movie by getting the cosine similarity of their latent representations.